|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOCIAL AND DOMESTIC HABITS.

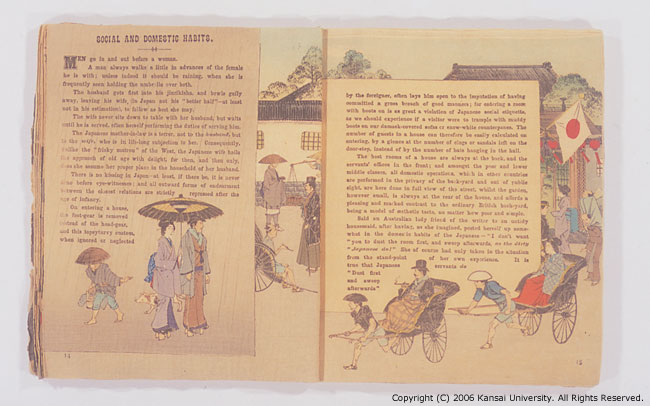

MEN go in and out before a woman. A man always walks a little in advances of the female he is with; unless indeed it should be raining, when she is frequently seen holding the umbrella over both. The husband gets first into his jinrikisha, and bowls gaily away, leaving his wife, (in Japan not his “bettter half”-at least not in his estimation), to follow as best she may. The wife never sits down to table with her husband, but waits until he is served, often herself performing the duties of serving him. The Japanese mother-in-law is a terror, not to the husband, but to the wife, who is in life-long subjection to her. Consequently, unlike the “frisky matron” of the West, the Japanese wife hails the approach of old age with delight, for then, and then only, does she assume her proper place in the household of her husband. There is no kissing in Japan-at least, if there be, it is never done before eye-witnesses; and all outward forms of endearment between the closest relations are strictly repressed after the age of infancy. On entering a house, the foot-gear is removed instead of the head-gear, and this topsyturvy custom, when ignored or neglected |

by the foreigner, often lays him open to the imputation of having committed a gross breach of good manners; for entering a room with boots on is as great a violation of Japanese social etiquette, as we should experience if a visitor were to trample with muddy boots on our damask-covered sofas or snow-white counterpanes. The number of guests in a house can therefore be easily calculated on entering, by a glance at the number of clogs or sandals left on the door-step, instead of by the number of hats hanging in the hall. The best rooms of a house are always at the back, and the servants' offices in the front; and amongst the poor and lower middle classes, all domestic operations, which in other countries are performed in the privacy of the back-yard and out of publie sight, are here done in full view of the street, whilst the garden, however small, is always at the rear of the house, and affords a pleasing and marked contrast to the ordinary British back-yard, being a model of aesthetic taste, no matter how poor and simple. Said an Australian lady friend of the writer to an untidy housemaid, after having, as she imagined, posted herself up somewhat in the domestic habits of the Japanese--“I don't want“ you to dust the room first, and sweep afterwards, as the dirty “Japanese do!” She of course had only taken in the situation from the stand-point of her own experience. It is true that Japanese servants do “Dust first and sweep afterwards” |

|||

|

||||

| Copyright (C) 2006 Kansai University. All Rights Reserved. | |